Should I contribute to a traditional or a Roth IRA?

This is a big question I get asked fairly frequently. And really, the conversation expands beyond individual retirement accounts. The decision whether to invest on a tax deferred or tax exempt basis is one you’ll likely make many times over your investing career. Some people prefer a exempt account to “get taxes out of the way”, while others prefer to defer taxes as long as possible in order to “let their money work for them”.

In this post we’ll explore the topic and discuss which situations may be best for either strategy. But first, let’s review exactly what tax deferred and tax exempt investing actually are.

Tax Deferred Investing

Thanks to our tax code and our government’s insistence that we save for our own retirement, American taxpayers have several different ways to save & invest on a tax deferred basis. Tax deferred means that you don’t pay income taxes on contributions to such accounts, by way of tax deduction. Down the road after you reach retirement age, taxes are assessed when funds are withdrawn from such accounts. In other words, you’re able to defer taxes until retirement.

Our tax code includes a few main ways to save for retirement on a tax deferred basis: individual retirement accounts (IRAs), “qualified” retirement plans like 401(k)s and 403(b)s, and annuities.

The best way to understand the benefits of tax deferred investing is to compare it to taxable investing. When you invest in a taxable account, you typically pay tax at three different levels:

- You pay income tax on your contributions

- You pay tax on dividends received in your account

- You pay tax on capital gains realized after selling assets at a gain

But in a tax deferred account, you avoid two of these three levels of taxation:

- You get an income tax deduction on contributions

- Your contributions grow tax free while they’re in the account (no tax on dividends or capital gains)

- You pay income tax only when you take withdrawals from the account later on

Here’s an Example:

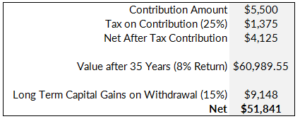

Let’s say you’re 25 years old, want to contribute $5500 to a traditional IRA, and plan to withdraw the funds in 35 years once you turn 60. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume you’re in the 25% tax bracket both now and when you withdraw the funds down the road.

If you were to invest this money in a taxable account, you’d pay 25% income tax on your contributions. Your investments would then grow over time (let’s assume at 8% per year). If you don’t sell them until you turn 60, you’d owe long term capital gains tax on the difference between the sale proceeds and your cost basis. And if you’re in the 25% tax bracket at that point, your long term capital gains would be taxed at 15%. (Here is the IRS breakdown for long term capital gains treatment).

But if you instead made a $5500 contribution to a traditional IRA, you wouldn’t pay income taxes on your initial contribution thanks to the tax deduction. Your investments would grow tax free, and you’d only be taxed on the income when you begin withdrawals after age 60:

Essentially, you’ve skipped two levels of tax by contributing to a traditional IRA: income tax on your contributions and gains & dividends during the growth phase. In short, the more tax you can avoid, the better off you’ll be.

Tax Exempt Investing

Tax exempt investing is essentially the opposite of tax deferred investing. Rather than pay tax on the withdrawals from your retirement account, a tax exempt account requires you to pay income tax on your contributions. These contributions then grow tax free over time, and your withdrawals can be taken tax free once you reach retirement age. Rather than paying tax on the “back end” in a tax deferred account, you pay tax on the “front end” in tax exempt accounts .

As you may already know, tax exempt investing is accomplished in a Roth account. Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k)s are the two main options here, and while they do have slightly different rules their tax treatment is the same.

Roth IRAs have strict income phaseout limits just like traditional IRAs. But with Roth IRAs, having an income above the phaseout limits prohibits you from making contributions entirely. With traditional IRAs, if your income falls above the phase out limits in a certain year you can still make contributions – they just won’t be deductible. This is an important difference, which we’ll address later in the post.

Here’s an Example:

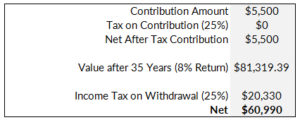

Take our previous example from above. Instead of contributing to a traditional IRA, let’s contribute the $5500 to a Roth IRA. Rather than pay taxes on withdrawals 35 years down the road, contributing to a Roth account allows us to “get the taxes out of the way now”:

Notice that the net amount after 35 years is the same in both the traditional and Roth IRA examples:

This is because we’re assuming the marginal tax rate will be the same in 35 years as it is now. Realistically, this probably isn’t true. While we don’t know exactly what bracket we’ll be in 35 years down the road (or what our tax structure will even look like then), most people expect to be in a higher bracket at age 60 or later than they are at age 25.

When Tax Deferred Investing Makes Sense

This brings us to the point. There’s a lot of talk out there surrounding whether it’s better to take the tax deduction now by contributing to a traditional IRA, or get our taxes out of the way by contributing to a Roth.

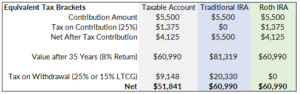

There are a few components to consider when making this decision, but let’s look at the math first. Thanks to our progressive tax structure, we can benefit from comparing our current tax bracket to our projected bracket when we begin withdrawals.

If you’re in the middle of your career and enjoying your peak earnings years, it’s likely you’re in a higher bracket now than you’ll be after you retire. And if that’s the case, taking the deduction now in a traditional IRA would be the most beneficial.

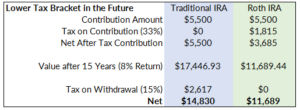

Earlier we assumed you’d be in the 25% bracket both now and when you began taking withdrawals. Instead, let’s assume in this example that you’re in the 33% now and expect to be in the 15% bracket during withdrawals. (I should note here that you’d exceed the income phaseout limits by virtue of being in the 33% bracket. In other words, if you were actually in the 33% bracket you couldn’t contribute to a Roth IRA or deduct your contribution to a traditional IRA. This example is simply to make a point).

As you can see, by contributing to a traditional IRA in the years your tax burden is higher you end up with a better result. Which makes total sense. If you have the choice between avoiding a 33% or a 15% tax, which would you choose? The 33% tax, of course!

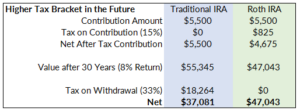

When Tax Exempt Investing Makes Sense

As we saw above, the math obviously favors avoiding tax in years we’re subject to a higher rate. So, if you expect your tax burden to be higher during your withdrawal period than it is now, the math favors “getting the tax out of the way” now. You could easily find yourself in this situation earlier on in your career, or maybe just following a career change when your income is lower:

Projecting Future Tax Liabilities

This is all a helpful discussion, but we don’t know what our tax burden will actually be down the road. Not only is it impossible to predict which bracket we might find ourselves in 10, 20, 30, or even 40 years down the road, we don’t even have a clue what our tax brackets will look like then.

At the end of the day, the best we can do is make an educated guess. Many pundits expect our aggregate level of taxation to increase over the long term, thanks to our high (and increasing) level of national debt. And for that reason some investors prefer to pay taxes now through Roth contributions, rationalizing that it’s better to pay the “devil they know” than the “devil they don’t.”

Required Minimum Distributions

Now that we have the math out of the way, it’s time to cover the other differences between tax deferred and tax exempt investing.

When you contribute to a traditional IRA, the government gives you a pass on paying income tax until you withdraw the funds in retirement. The catch here is that even if you’d prefer to keep your money growing inside the IRA (or other tax deferred account), Uncle Sam will eventually want his cut and force your hand.

Once you turn 70 1/2 you’ll be forced to begin taking required minimum distributions (or RMDs). This means you’ll need to take withdrawals from your tax deferred accounts each year based on your life expectancy and account balances, and pay income tax accordingly.

For many taxpayers this is pretty inconvenient. If you’re in a position where you don’t need the funds to live and are more focused on maximizing your long term wealth, you’d likely prefer to let your savings continue growing tax deferred. RMD’s throw a monkey wrench into the equation, since you’re assessed a massive 50% penalty if you miss one.

Roth IRAs don’t have this imposition. Since you pay taxes when you contribute to the account, there’s nothing else the government is waiting to collect. For that reason Roth IRAs do not have RMDs, meaning your savings can grow tax free for the rest of your life. (Side note – Roth 401(k)s often do have RMDs, but these accounts can easily be rolled over into a Roth IRA).

Issues for Beneficiaries

The other main issue is what your tax deferred vs. tax exempt choice means for your beneficiaries. After you die, the beneficiaries of your account will have a couple different options surrounding how they handle the inheritance. Spouses can treat the accounts as if they were their own. But if you decide to bequeath your assets to anyone other than your spouse, that person (or those people) will be forced to withdraw the funds in one of a few different ways. This might be immediately, within 5 years, or over their own lifetime. The exact rules depend on the circumstances, which can you can read about on the IRS website here.

The key is whether or not these required withdrawals on inherited accounts are taxable. When your beneficiaries inherit a traditional IRA, they’ll owe income taxes on the amounts withdrawn – remember, the government still wants its cut. But if they inherit a Roth IRA, they won’t. You’ve already paid the tax for them when you contributed to the account.

This is an important point – especially if your objective is to maximize your family’s multi-generational wealth. When you’re trying to decide whether to contribute to a traditional or Roth account, the decision goes beyond your lifetime. By contributing to a Roth IRA, you not only “get the tax burden out of the way” for yourself – you also pay it for the rest of your family.

Tax Deferred & Tax Exempt Investing in the Real World

In a perfect world we’d contribute to a Roth IRA in years when we expect our future tax bracket to be higher than it is now, and traditional IRAs in year where the reverse is true. But in reality, we need to remember that both traditional and Roth IRAs have income phaseouts. It’s entirely possible that you may be unable to contribute to a Roth IRA (and deduct contributions to a traditional IRA) as your income grows beyond these limits.

In other words, many Americans will encounter situations where they simply don’t need to make the choice between contributing to a tax deferred or tax exempt account. Their only option will be to make non-deductible contributions to traditional IRAs.

This being the case, most people will be better off funding a Roth IRA earlier in their careers. Then as your income starts to build and you approach the phaseout limits, you can begin contributing to a traditional IRA when you’re absolutely sure your future tax bracket will be lower. And, if you eventually exceed the phase-out limits, making non-deductible contributions to a traditional IRA is still a great option (and an opportunity for “back door” Roth conversions, which I’ll cover in a future post).

To Summarize

In a perfect world, we’d know exactly what our tax liabilities would look like every year until we died. We don’t. In fact, when we start thinking about what our country’s tax structure or our personal picture might look like years down the road, the exercise almost becomes pointless.

As a rule of thumb, I’m of the opinion that most of us should lean toward tax exempt investing in Roth IRAs, for a few reasons:

- Our long term taxation level is more likely to be higher than lower

- Roth IRAs don’t have required minimum distributions

- It gives us the opportunity to put away money tax free for our lifetime AND our beneficiaries’ lifetime

Tax deferred investing is a great option too. But in most cases, unless you were absolutely sure you’d be in a significantly lower tax bracket in retirement than you’re in now, the Roth IRA is probably the better choice.

What do you think? Is tax exempt or tax deferred investing better for you? How come?