Often when I bring up the idea of retirement “gap years” in meetings, my clients’ minds wander toward a family member who’s decided to take a year off between high school and college. Then they shake their head in disbelief about how millenials are often encouraged to backpack around for a year to mature and “find themselves”. Another moment of reflection about how the world’s changed, and that’s about when their attention snaps back to refocus on our meeting.

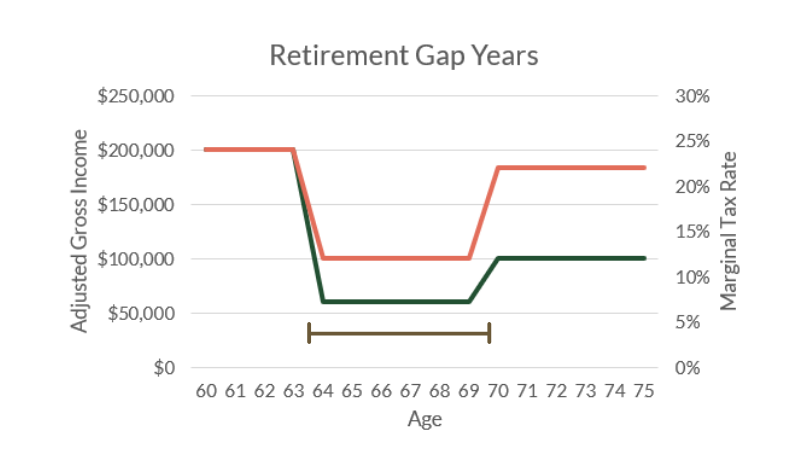

No, retirement gap years don’t have anything do with finding yourself or maturing. They have to do with the years between retirement and age 70. Many people will see their taxable income fall to lower levels once they stop working, and spike once they turn 70. Thus, the retirement income “gap”.

Here’s why. For those of us with assets in qualified retirement accounts like 401(k) plans or IRAs, 70.5 is the age when the IRS begins imposing mandatory distributions, which will be added to your taxable income. Once you begin collecting Social Security you’ll also be taxed on either 50% or 85% of the benefits, depending on where that taxable income falls. If you’re one of the many people waiting until age 70 to collect, that’s two extra sources of taxable income added simultaneously, and recurring every year thereafter.

Thanks to our progressive tax system, the years you find yourself in a lower tax bracket can be a great opportunity to reduce taxes over the rest of your life. This post will explore how.

The Opportunity

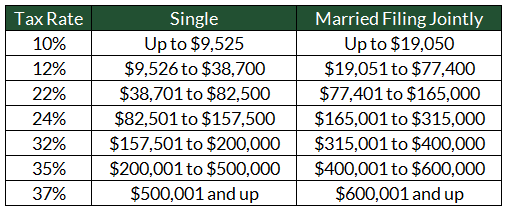

As you know, we have a progressive tax system here in the U.S. The higher your taxable income, the higher the rate you pay. As I write this, the tax brackets for single & married people filing jointly are:

Notice the big jumps here – our marginal tax rates don’t increase evenly. 10% & 12%, 22% & 24%, and then 32% and higher. The increases from 12% to 22%, and again from 24% to 32% are significant, and present a convenient opportunity when planning for retirement.

Think of a typical retirement timeline. If you plan to stop working at 65 years of age, chances are your taxable income will be higher at age 64 than it will be at age 66. Then a few years later at age 70.5, you’ll enter RMD territory. The IRS will force you to take a certain amount of money out of your tax deferred retirement accounts every year, or face a stiff 50% penalty.

On top of this, if you’re eligible for Social Security benefits you’ll begin collecting on them sometime between 65 and 70. So, if you decide to postpone for as long as possible, your RMDs will occur in the same year you begin collecting Social Security benefits. And after seeing your taxable income fall (potentially into a lower bracket) after you stop working, it’ll jump once you turn 70.

The opportunity here lies in this temporary reduction in taxable income. If you fall into a lower bracket, accelerating taxable events makes a lot of sense since you’d be paying tax at lower rates. In other words, the idea is to “fill up” the lower brackets whenever possible.

Strategies

There are many ways to “accelerate” income in the years you find yourself in a lower tax bracket. And if you can project your tax liability throughout the year you can accomplish this with some precision. Here are three ideas to consider.

Roth IRA Conversions

The most straightforward way to take advantage of your retirement gap years is to convert tax deferred retirement assets to a Roth IRA. As you probably know, your contributions to 401(k) or 403(b) plans are deductible when you make the contribution. (In fact, your contributions don’t even show up on your W-2). IRA contributions are also deductible if your income isn’t too high. Then when it comes time to take money out, the amount withdrawn minus basis is added to your taxable income for the year.

As you may also know, Roth IRAs have the opposite treatment. There’s no deduction on your contributions. But, funds in a Roth IRA grow tax free forever. You’re never compelled to take withdrawals if you don’t want to (since the IRS has already taken its cut), and if you do those withdrawals come out tax free.

While I’m a huge fan of the Roth IRA for retirement savings purposes, the IRS also acknowledges that it’s a great deal. So much so that they prohibit you from making contributions if your adjusted gross income falls above certain thresholds ($137,000 for single filers and $203,000 for married people filing jointly in 2019).

However, while many people are prohibited from contributing to Roth IRAs because their income is too high, there’s no limit on conversions. Rather than depositing funds into a Roth IRA directly, you can always convert funds already sitting in another tax deferred retirement account to a Roth IRA. Just like withdrawals, the market value of what you convert, minus basis, is added to your taxable income for the year.

There are a couple benefits of executing Roth IRA conversions during your gap years. First, if you’ve fallen into a lower tax bracket you’d be paying tax on the assets at a lower rate than if you’d waited until age 70. On top of that, you’d be getting tax out of the way FOREVER. Regardless of whether you leave the money in the account to grow or withdraw it, funds in a Roth IRA are never taxed again. Ever. Even better, if you bequeath the account to your kids they never pay tax on withdrawals either. It’s a tremendous deal from a tax standpoint, which is exactly why the IRS limits our contributions.

Additionally, by converting tax deferred assets to a Roth IRA, you’re shrinking the pool of money subject to mandatory distributions once you turn 70.5. This can be very convenient later on. Not only are you getting funds into a tax free account, you’re giving yourself more flexibility when RMDs do come knocking. I’d much rather have the choice between pulling extra funds (in excess of my RMD) from an IRA that I’ll be taxed on, or taking a tax free withdrawal from a Roth IRA on top of my RMD.

Harvesting Long Term Capital Gains

Along the same lines, you may have some unrealized capital gains on taxable investments. Appreciated securities in taxable investment accounts, real estate, and investments or business interests are subject to capital gains taxes based on how long you’ve held the position.

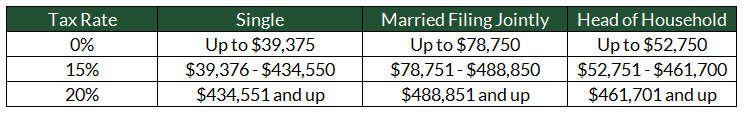

Harvesting short term capital gains in the retirement gap years does make a lot of sense. Gains on investments held less than one year are taxed at short term capital gains rates, which are exactly the same as ordinary income rates. But the opportunity will more likely lie in long term holdings with bigger gains. Long term capital gains rates are applied on investments held for longer than one year, and are either 20%, 15%, or 0%. The exact rate depends on your taxable income:

Note here that long term capital gains are added to your taxable income for the year. So if you’re married with taxable income of $75,000 in your first year after retirement, you can’t turn around and sell $500,000 worth of stock at a 0% rate. You could sell $78,750 – $75,000 = $3,750 at 0%. That said, if you did fall into the 0% long term capital gains territory, harvesting gains at 0% could be extremely beneficial. Even if it is only $3,750.

Avoiding Net Investment Income Tax

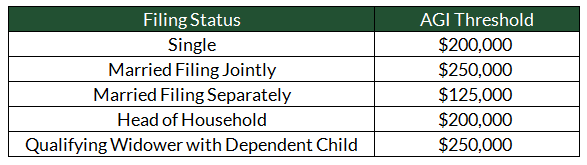

On top of progressive marginal income and long term capital gains rates, higher income taxpayers are subject to the net investment income tax rate. If your modified adjusted gross income is above a certain amount, you’ll be subject to an additional 3.8% tax on investment income. This tax is imposed on interest, dividends, and capital gains from a wide variety of investments. Stocks, bond, annuities, rental real estate, royalties, business interests….all are considered investment income for the purposes of this tax.

Seeing as how you usually have a lot of control over your investments, you also have a good deal of control over your investment income. Whether it’s harvesting long term gains on appreciated positions, moving toward a higher income bond or dividend paying stock portfolio, or perhaps distributing profits from a business you own, if you’re subject to the 3.8% NII tax and about to stop working, you may want to wait until your MAGI falls.

[Click Here to Download the Retirement Readiness Checklist]

Example

Let’s run through an example that’s relatively common in my practice. Say you earn $200,000 in W-2 income while you’re employed. You’re married, and take the standard deduction of $24,000. Your adjusted gross income would be $200k, and your taxable income would come in at $200,000 – $24,000 = $176,000. You’d find yourself in the 24% tax bracket.

For savings, let’s say you’ve amassed $700,000 in your company 401(k), and have another $450,000 in a taxable brokerage account. You think you’ll need $65,000 per year to live on in retirement, and plan to wait until age 70 to collect Social Security, at which point you’ll be entitled to a benefit of $2,650 per month.

With this fact pattern, your withdrawal rate would be $65,000 / ($850,000 + $450,000) = 5% at first. It’d then fall back down to 2.6% once you begin collecting Social Security benefits: $65,000 – ($2,650 * 12) / ($850,000 + $450,000).

If you retired at 65 you’d have a retirement gap of five years. To raise $65,000 per year to live off, you could pull the funds from your IRA (adding the full $65,000 to your taxable income), your taxable account (adding the capital gains to your taxable income) or some combination of both. In general you’ll have a better outcome by withdrawing from your taxable account first, and allowing your retirement accounts to compound tax deferred.

In this case, doing so would drop you into a significantly lower bracket. If you’re pulling from your taxable account first, the capital gains on securities sold won’t exceed $65,000 – and will probably be much lower. At $65,000 of adjusted gross income you’re looking at a max of $41,000 of taxable income after taking the $24,000 standard deduction. Meaning, you’d fall from the 24% tax bracket all the way to the 0%, 10%, or 12% bracket.

Since the 22% bracket doesn’t kick in until $77,401 of taxable income, you could convert at least $36,401 ($77,401 – $41,000) of your tax deferred account per year to a Roth IRA at 12%.

At age 70 you’d add Social Security benefits of $31,800 ($2,650 * 12) and distributions from your 401(k) / IRA to the mix. Assuming your retirement account grows at 7% per year, your first mandatory distribution would be $40,183.

So at this point you’d be looking at a minimum of $71,983 of set cash flow: $31,800 from Social Security and $40,183 from your retirement account. Since 85% of your Social Security benefits would be taxable, your adjusted gross income would come in at $67,212. While you’d have some room before bumping up into the 22% bracket, it’s not hard to imagine an event that adds $10,000 to your taxable income for the year. Converting your tax deferred savings to a Roth IRA gives you some flexibility when deciding which account to withdraw from, and helps reduce your RMDs.

In Practice

After doing this in my practice for a while, I have two observations that might be helpful. First, while it’s nice to incorporates strategic Roth IRA conversions during your gap years, life always evolves a little differently than we anticipate. This makes mid-year tax projections really important. Don’t add to your taxable income before understanding what it’d be in the first place.

It’s no big deal if your Roth conversions bump you a few thousand dollars into the next bracket. The higher tax rate is only applied to the amount that’s in that bracket. But surpassing the NIIT limits means the extra 3.8% will apply to ALL your investment income. (With an exception or two). I’d hate to tack on an extra 3.8% across the board just because a tax projection wasn’t perfect (or wasn’t performed at all). So run a projection mid-year, and give yourself some room if you’re approaching the NIIT threshold.

Second, Roth IRA conversions tend to have the largest impact over time when compared to the other strategies listed above. Usually I like to take any opportunity to get assets into Roth accounts at lower tax rates. If it’s a choice between harvesting a long term gain and a Roth IRA conversion, I’m ringing the bell on the conversion almost every single time. And in my world it’s rare that someone I’m speaking with doesn’t have at least something in a tax deferred account.

But at the end of the day, it all comes down to planning. Transitioning into retirement really requires a thoughtful plan. When you have the plan in place, it’s not difficult to see opportunities during your retirement gap years.

What do you think?

Have you considered Roth IRA conversions during your retirement gap years?

What worked or didn’t work for you?