Taxes are frustrating to nearly every small business owner I speak with. Most people agree that we should all pay our fair share. But after working countless thousands of hours to build a viable business, it’s easy to feel like Uncle Sam’s reaching into our pockets too far. That’s why I focus on helping my clients who own businesses make sure they’re not paying more in taxes than they need to. One great tool we can use in this endeavor is a defined benefit retirement plan. Whatever you want to call it, DB plan, defined benefits pension plan, etc., it can be a killer way to defer a huge portion of your income from taxation.

I realize you might cringe when you read the words “pension” or “defined benefit”. The idea of promising employees a monthly check throughout their retirement may not foster warm and fuzzies. But if you don’t have employees, or only have a few, a defined benefit plan can offer some pretty major tax advantages.

Read on to learn how you might take advantage of them.

Defined Benefits: The Backstory

Defined benefit plans have been around forever, and even date all the way back to the 1800s. We can thank their modern form, though, to ERISA: the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. You’ve probably heard of ERISA. The legislation created “qualified” retirement plans, like the 401(k) and other defined contribution plans. By “sponsoring” one through a business, we’re allowed to defer income tax on contributions to retirement accounts – at both the personal and corporate levels.

Qualified plans generally fall into two categories: defined contribution and defined benefit. In a defined contribution plan, like a 401(k), there is a limitation on how much you and your employees can contribute to the plan every year. There’s no limit to how large the account can grow, though.

A defined benefit plan is just the opposite. There’s no limit on how much you can contribute to the plan. Instead, you define the benefits the plan will pay to you and your employees through retirement. The IRS establishes a limit to this amount, which in 2017 is $215,000. You then contribute enough to the plan every year so that it grows large enough to pay the benefits you’ve “defined”. This amount is determined by an actuarial calculation every year, and is of course tax deductible.

Mandatory Contributions

When you establish a plan, one of the first decisions you make is the plan’s payout formula, or how much you and eligible employees will receive each year after retirement. Usually this is based on a combination of service with your company and a percentage of compensation.

Then you get to calculate your contribution for the year. (However, in nearly all cases an actuary or third party administrator would do this work for you). Whoever runs the calculation makes assumptions surrounding who will draw from the plan, when, how much, and what the plan’s investment returns will probably be. They then apply those assumptions every year to determine how much you need to contribute.

With a defined benefit plan, your contributions are mandatory. By establishing the plan you’re promising eligible employees a certain amount of retirement benefits. You’re then expected to make good on those promises by funding the plan adequately so it can afford to pay them.

Your contributions each year will fluctuate based on the plan’s investment performance and the demographics of your eligible workforce. If you make ten new hires who are eligible for your plan immediately, you’ll need to make a significant contribution on their behalf. But, if your plan’s asset saw incredible returns from the previous year, you could build up enough of a “padding” to offset the extra cost.

Here’s Where You Can Stack Up the Tax Deferrals

If defined benefit plans sound complicated, that’s because they are. Defined benefit plans take a good deal of oversight to run effectively and in a compliant manner. But in some circumstances, the tax advantages can be well worth the headache.

When you have more than a few employees, establishing a defined benefit plan might be a bigger responsibility than you want to bite off. But if you only have a couple, most of your annual contributions will be used to fund your personal benefits. And if you don’t have any, you get to the reap the full tax benefits without the ongoing obligation to make contributions for anyone else.

Not Sold Yet? Here’s an Example:

OK, so let’s say you’re a 55 year old small business owner. You have a few contractors that work for you but none are full time employees – all work less than 1,000 per year.

You’ve built a great business over the years, but haven’t saved anything for retirement. You love what you do, but don’t want to work forever. Long story short, you need to make up for lost time.

Let’s say you make $260,000 per year. You could set up a SEP-IRA or Solo 401(k) and contribute the annual max ($53,000 in 2016 / $54,000 in 2017). But if your plan is to stop working in 10 years, $54,000 in annual contributions won’t be enough. $54k per year, growing at 7%, would work out to $746,088 by the time you’re 65.

That’s probably well short of what you’d need to retire. If you planned to spend $75,000 per year through retirement, you’d need $100,000 in pretax retirement funds if you’re in the 25% tax bracket. Remember – you pay income tax on anything you withdraw from a tax deferred account (like a SEP-IRA or 401k). So if you need $75,000 per year to live, that means you’d need to withdraw $100,000 in pretax dollars in order to have $75,000 after tax ($100,000 * (100% – 25% = $75,000). Using the “back of the envelope” 4% rule, that means you’d need to accumulate $100,000 / 4% = $2,500,000.

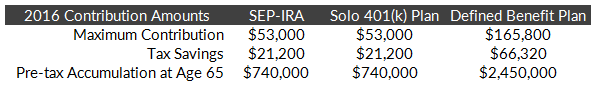

Now let’s say that you consider a defined benefit plan instead. Making a few assumptions listed below, you could contribute $165,800 to your plan in 2016, and slightly more than that in 2017. That means you’re shielding $112,800 more from taxation than you would in a SEP-IRA or Solo 401(k).

Here’s the breakdown:

Assumptions: 40% tax bracket, SEP-IRA & Solo 401(k) appreciate at 6% per year, DB plan appreciates at 3.98% before age 65 & 5.5% thereafter.

Thanks to the higher contribution limits of a defined benefit plan, you could shield $165,800 from tax. That’s a tax savings of $66,320, or $45,120 more than you’d get through a SEP-IRA or Solo 401(k).

Who DB Plans Work Best For

The defined benefits pension plan isn’t for everyone. If you have full time employees they’ll probably be eligible for your plan, meaning you’ll need to make contributions on their behalf too. Whether you view that as an employee attraction/retention tool or as an additional cost, the dollars add up. There are some specific conditions where DB plans work very well though, and they have to do with your workforce, your income, and your age:

Employees

Like the example above, defined benefit plans are most beneficial to business owners who don’t have employees consider. Since defined benefits are “qualified” pension plans, you’re required to enroll all eligible employees in the plan. That means you must include employees who:

- Work at least 1,000 hours per year

- Are at least 21 years old, and

- Have at least one year of service

The one year of service requirement can be pushed to two years (which is an option for all qualified plans other than 401(k) plans). But in doing so, your contributions must vest immediately. Most defined benefit plans prefer to stretch out vesting over a longer time frame. That way you’re not stuck paying for the retirement benefits of employees who only work with you for a short time.

It’s for this reason that defined benefit plans work great for solo business owners. But in many circumstances they can also work well if you have no more than five employees. When you add more employees to the mix, things get complicated and expensive really quickly.

Income

One of the chief advantages to defined benefit pension plans is their high annual contribution limit. Remember – you set the level of annual retirement benefits. Your mandatory contribution is simply the amount necessary to provide that annual amount.

Defined benefit plans are also a little more costly to operate. So to be better off with a defined benefit plan you really need to take advantage of the high annual contributions, above the $54,000 offered in other plans. If you don’t have the income to contribute more than this amount, you’re probably better off with a less expensive defined contribution plan. Usually that means you need to make at least $250,000 or so per year, through your business.

Age

Age plays a big factor here too. If you’re getting a late start on saving for retirement, the high tax advantaged contributions can get you caught up quickly. But if you’re earlier in your career, the contributions of a defined benefit plan won’t be that much higher than the annual limits you’ll find from a defined contribution plan. And with the higher operating costs, a defined benefit plan probably doesn’t make much sense.

Age 50 is a good rule of thumb here. If you’re 50 or older, a defined benefit plan might warrant further consideration.

Pros of Defined Benefits Pension Plans

- Higher contribution & deduction levels. Tax savings, baby! Obviously, this is the biggest advantage. Defined benefit plans aren’t meant to be used as a tax shelter, but since your contributions are deductible they’re still a killer way to lower your tax bill.

- Prior service. In defined contribution plans you’re only able to make deductible contributions after establishing the plan. In defined benefits pension plans, you can count prior service at your company when determining benefits. This especially gives you more flexibility if you have employees. Prior service thresholds can be a tool you can use to maximize your personal contributions while minimizing the cost of employee benefits – if that’s your thing.

Cons of Defined Benefits Pension Plans

- Complexity. Defined benefits pension plans are more complicated to administer than defined contribution plans. You need to run actuarial calculations on a regular basis to determine your annual contribution requirements. These benefit formulas can be pretty complex, so most sponsors prefer to hire someone. Unless you’re well versed in pension law and ERISA, my strong recommendation is to go this route.

- Cost. If you decide to hire an actuary or third party administrator to help operate your plan (again, please do), the costs can add up. Normally service providers will charge a set up fee, plus ongoing administration fees to cover annual contribution calculations and employee communication.

- Mandatory Contributions. Once you establish a plan, you’re agreeing to fund it with whatever contributions are necessary every single year. If the market crashes, you’ll need to make a larger contribution the following year to make up for lost growth. Defined benefit plans don’t bend for business performance, either. Whereas in a defined contribution plan you could suspend profit sharing contributions during tough times, you’ll be need to make contributions to a defined benefit plan no matter what.

- Communication. Defined benefits pension plans can be difficult to communicate to employees too, due to their complexity. Plus, if you do have employees they might prefer a 401(k) plan since they have more control over the accumulation and outcome.

If you’re 50 or older, have no more than a few employees, and are making at least $250,000 in self employment income, a defined benefits pension plan could be a good way to reduce your tax burden. Just keep in mind that this type of plan is just one tool in your toolbox. To use it effectively you need a more comprehensive blueprint that integrates tax planning with the all other areas of your financial life.