Incentive stock options are a wonderful benefit to receive. They’re often granted to executives of publicly traded companies and early stage employees of startups, in an effort to align their interests more closely with shareholders. They’re also more complicated than their close cousins, non-qualified stock options thanks to certain tax advantages. The timing of when your shares vest, when you exercise, and when & whether you sell the resulting shares determine how your options are taxed & whether these advantages will apply. This post will cover the basics of incentive stock options, how they’re taxed, and a few points to consider if you’ve been granted them.

The Basics of Incentive Stock Options

Stock options give holders the right to buy or sell a certain security at a certain price for a certain period of time. You can buy and sell stock options on thousands of publicly traded stocks through a typical brokerage account. Incentive stock options are the same basic contract, where you’re given the right to buy a certain number of shares of your company for a specific dollar amount. Here are a few basic terms you’ll need to know.

Strike Price: This is the price at which you have the right to purchase shares. This is often discounted from the current market price.

Fair Market Value: Fair market value (FMV) reflects the value of a company’s shares at any given time. This is easy to ascertain for large, publicly traded companies since their equity value is constantly being traded over exchanges. FMV for a given day is simply the average of the high and low selling prices on a particular trading day. For privately held businesses, FMV is typically determined by a formal appraisal or business valuation.

Vesting: Vesting is the concept of your options becoming “active”. Often companies will issue stock options that vest over time. This incentivizes employees to stick around and continue building the value of the company. A common vesting schedule might be 25% over four years. This means that if you’re issued 1,000 options, 250 will be available for you to exercise one year after the grant date. Another 250 would vest after two years, and so on. Another common schedule for ISOs is a three year cliff, where none of the options vest for the first three years. Then when the three year date arrives, 100% vest.

Grant Date: This is the date the company gives you the options initially. Vesting “clocks” start ticking on the grant date.

Expiration Date: This is the date the options expire. Note that sometimes expiration is triggered upon resignation or termination of employment. Usually you’ll have 90 days after leaving to exercise your options, but this isn’t always the case.

Bargain Element: The difference between the fair market value of the shares and your strike price is the bargain element.

Qualifying Disposition: If you sell ISO shares at least two years after the grant date and one year after exercising, it’s considered a qualifying disposition. This comes with favorable tax advantages.

Disqualifying Disposition: Any sales of ISO shares that are not considered qualifying dispositions are considered disqualifying dispositions. Disqualifying dispositions are taxed differently.

Example:

Let’s say that your employer gave you 1,000 incentive stock options three years ago that just vested. The strike price (exercise price) is $10, and equity shares of your company currently trade over an exchange at $25. The bargain element works out to $15 per share: $25 – $10. Even though shares of your company might cost $25 on the open market, your ISOs give you the right to buy them for $10. If you exercised your options and hung onto them for one year, you could then sell the shares in a qualifying disposition. Exercising and immediately selling would be considered a disqualifying disposition.

Taxation of Incentive Stock Options

With ISOs the first taxable event occurs when shares are exercised. There is no tax due when the options are granted, and none due when they vest. The treatment of how they’re taxed depends on whether share sales are considered qualifying or disqualifying dispositions.

Qualifying Dispositions

As described above, qualifying dispositions of ISOs are any share sales that occur at least two years after grant date AND one year after exercise. Sales of ISO shares that don’t fit this description are considered disqualifying dispositions.

In a qualifying disposition, both the bargain element of the options and the capital gain are taxed at long term capital gains tax rates. This can be tremendously beneficial, as long term capital gains are currently taxed at substantially lower rates than ordinary income.

That’s not all though. In addition to long term capital gains, the bargain element is considered a preference item for the alternative minimum tax. By exercising and not selling, even though you wouldn’t be paying any capital gains taxes yet, it’s still possible that you’d owe tax at exercise.

Disqualifying Dispositions

Disqualifying dispositions are taxed differently. Rather than adding the bargain element as an AMT preference item, the difference between fair market value and your exercise price is considered earned income, taxed at your ordinary income tax rate. Any gains between your exercise date and the date you sell are then considered capital gains, and taxed based on your tax bracket and amount of time you hold the shares.

Capital Gains

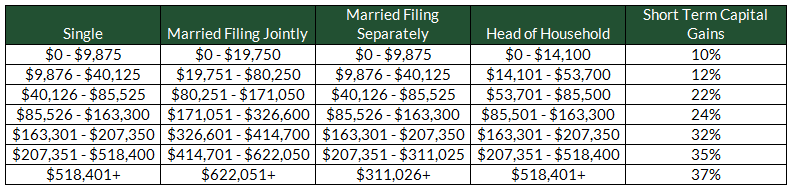

Having the bargain element AND gains taxed at long term capital gains rates is a huge potential tax advantage. As a reminder, gains on any investments held for less than one year are considered short term capital gains. Short term gains are taxed at the same rate as your ordinary income. Here are the brackets for 2020:

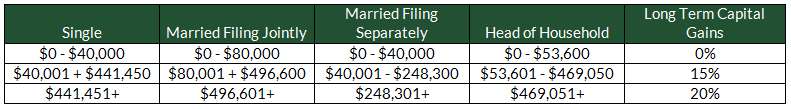

Gains on investments held for longer than one year are considered long term capital gains, and qualify for lower tax rates:

Here’s an Example:

Continuing the previous example, let’s say that you’re granted 1,000 ISOs at a strike price of $10 and a three year cliff vesting schedule. Let’s also say that you decide to exercise all the options immediately upon vesting when the fair market value is $25 per share, and you’re in the 32% tax bracket.

If you sold all the shares immediately (for the FMV of $25 per share), it’d be considered a disqualifying disposition since you held them for less than one year after exercise. This being the case the bargain element would be considered ordinary income. You’d owe (($25 – $10) * 1,000) * 32% = $4,800 of federal income tax.

What would the impact be if you exercised the shares but hung onto them, shooting for a disqualifying disposition? First off, the bargain element would be considered an AMT preference item in the year of exercise. This may impact your tax bill, it may not. But assuming the FMV of the shares doesn’t change in the year after exercise, the bargain element would be considered a long term capital gain. (As would any appreciation). And rather than paying $4,800 in federal income tax, you’d be on the hook for (($25 – $10) * 1,000) * 15% = $2,250.

Alternative Minimum Tax Implications

The difference between qualifying and disqualifying dispositions brings up a challenging question for planning purposes. Is waiting around for a qualifying disposition worth it? The tax savings are compelling, but in exchange for long term capital gains treatment of the bargain element, you’re stuck with an AMT preference item in the year you wait. And by doing so, you take the risk that your shares fall in value over that twelve month period.

The AMT preference item won’t impact everyone. But it’s an important point to consider in your ISO planning. There is good news, too. When you end up selling the shares later in a qualifying disposition, the bargain element you had to include as an AMT preference item is added back as an AMT credit. This works to help you recoup some of the AMT taxes paid in the year of exercise. Potentially all of it, in fact. So while you may end up paying AMT while planning for qualifying dispositions, there’s a good chance you’ll get at least some of that AMT back after selling the shares.

Incentive Stock Option Planning Implications

Here are a couple common questions we get from people who’ve just received ISOs, as well as a couple questions we recommend you ask yourself before taking action:

Do You Have the Cash?

Before exercising ANYTHING, make sure you understand the tax ramifications and whether you plan to pony up the cash for the shares. If you don’t want to use cash out of pocket to exercise your options at the strike price, you’ll probably want to consider a cashless exercise. In a cashless exercise you’ll exercise and immediately sell additional shares, using the cash raised to pay the strike price for others.

Using our example above, if you’re exercising options on 100 shares of your company stock at a fair market value and $25 and strike price of $10, you’ll need to come up with $10 * 100 = $1000. If you exercised additional options to raise that cash, you’d need to exercise & sell another $1000 / ($25 – $10) = 67 shares.

The downside of cashless exercise is that it’ll trigger a disqualifying disposition on the shares sold to raise cash. If your intention is to exercise 100 shares of company stock at a fair market value of $25 and strike price of $10, you’d be triggering either:

- ($25 – $10) * 100 = $1,500 of w-2 income, if you sell the shares within one year of exercise; or

- An AMT preference item of ($25 – $10) * 100 = $1500, if you hang onto the shares after exercise

If you wanted to use a cashless exercise to avoid coming up with the $1,000 cash, you’d need to exercise and sell an additional 67 in a disqualifying disposition. This would add another (($25 – $10) * 67) = $1005 of taxable income. Just for avoiding the nuisance of going out of pocket to buy the initial 100 shares.

Should You Make an 83(b) Election?

Making an “83(b)” election is a popular strategy that allows you trigger a taxable event and exercise before your options actually vest. This can be beneficial if you believe your company’s stock price is poised to jump before your options vest. And by exercising early before the shares appreciate, you reduce the amount of potential AMT (or income tax) consequences.

The 83(b) election itself relates to a section of the tax code that allows for this type of maneuver. Note though that while the tax code allows incentive stock option plans to offer these elections to participants, ISO plans don’t necessarily have to. It’s a choice made by individual plans, described in its plan document.. This means you need to check with your plan to determine whether it’s available if you think you’d be a good candidate.

There are downsides to this strategy, too. If the shares don’t end up appreciating (or worse, fizzle out and fall substantially) you’ll have paid an unnecessary amount of tax. But in the right circumstances an 83b election can be a compelling option.

Are You Planning on Leaving the Company?

Once you leave your company, either voluntarily or otherwise, you typically have 90 days to exercise your vested options. After that date incentive stock options typically expire. This is a worst possible scenario. As important as it is to manage tax liability, taking advantage of your options’ bargain element still comes first. If that means tallying up a big tax bill right after you leave your employer, so be it. I’d much rather make a buck and pay tax on it than let the options expire worthless.

That being the case, a common ISO strategy is to exercise vested options consistently over time. That opens the door on long term capital gains rates, and keeps your unexercised options at a minimum.