Income based student loan repayment (or IBR) is one of the four income based repayment options that the federal government offers to help borrowers reduce monthly payments on their debt. IBR is a great option if you don’t qualify for the Pay as You Earn (PAYE) program, and aren’t a good fit for the Revised Pay as You Earn (REPAYE) program. While only available on certain federal student loans, the program is a wonderful benefit to many lower income borrowers.

What is Income Based Student Loan Repayment?

The income based repayment option (IBR) was originally passed by Congress in 2007, but didn’t become effective until 2009. It’s objective was to provide a more affordable student loan repayment option to low income borrowers. The plan improved on the preexisting income contingent repayment option (ICR) by lowering minimum monthly payments from 20% of discretionary income to 15%.

Then in 2014, IBR was revised. For new borrowers as of July 1st, 2014, monthly minimum payments were reduced from 15% of discretionary income to 10%, and the forgiveness period was shortened from 25 years to 20.

IBR was a significant improvement over the ICR repayment option. But today, there are two additional income driven repayment options (REPAYE and PAYE) that are a better choice for most borrowers. But due to PAYE‘s qualification standards and REPAYE’s mandatory inclusion of spousal income, IBR remains a viable option for many others.

How it Works

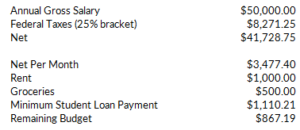

Like all income based repayment options, IBR gives borrowers an alternative if the minimum monthly payment on the 10 year repayment plan is too much. For example, let’s say you’re a new graduate and have accumulated $100,000 in federal student loan debt. You’re about to start work at job that pays $50,000 per year, and the interest rate on your loans is 6%.

Under the standard 10-year repayment plan, your minimum monthly payment would be $1,110.21. This is a huge amount, relative to your gross monthly pay of $4,166.67. After taxes, rent, and groceries of $500, you’d only have $867 per month left in the budget. That’s not much spending money, considering we haven’t included a cell phone, transportation, utilities, cable/internet, or any other discretionary expenses:

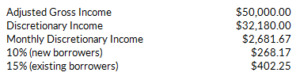

Enter IBR. If you qualify for IBR as a new borrower, your minimum monthly payment could be reduced to 10% of your discretionary income (15% if you qualify but are not a new borrower):

Obviously, paying $268.17 or $402.25 per month instead of $1110.21 gives you more flexibility in your budget. It will also take far longer to repay your loan though, and if your minimum monthly payment is less than the interest that accrues each month you won’t even make a dent in your principal.

Fortunately, if you continue making payments in the IBR system for many years, your loan balance will eventually be forgiven – 20 years for new borrowers or 25 years for existing borrowers. So, even if you remained at a $50,000 salary throughout your career and never paid off any principal, your loans would be forgiven down the road. Unfortunately, the amount forgiven would be taxable as income (unless the forgiveness qualifies for PSLF).

Discretionary Income

You’ll notice that the minimum monthly payment under IBR is based on 10% or 15% of discretionary income. Discretionary income is defined as the difference between your adjusted gross income based on your most recent tax return and 150% of the poverty line in your area. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services issues poverty guidelines geographically. They lump together the contiguous 48 states and Washington D.C., but set a slightly higher poverty line for Alaska and Hawaii since both have slightly higher costs of living. You can look up the poverty line in your area here.

For our example, the poverty line for one person households in the contiguous 48 states is $11,880. 150% of this amount is $17,820. That means an adjusted gross income of $50,000 would lead to $32,180 in discretionary income.

This is another improvement over the income contingent repayment option. ICR also calculates monthly payments using a percentage of discretionary income, but the definition is different. ICR uses the difference between your adjusted gross income and 100% of the federal poverty line, rather than 150%. The higher baseline of IBR works to reduce discretionary income further, resulting in a lower monthly payment.

Spouses

If you’re married, you’ll need to include your spouse’s income in your calculation of discretionary income if you file your taxes jointly. By filing “married filing separately” you can exclude their income, which is a nice feature of IBR.

It does come with other tax implications though. Generally you’ll pay more income tax when filing separately than you would filing jointly. This means your debt to income ratio would need to be pretty high in order for this move to make sense. Additionally, if you file separately you can’t contribute to a Roth IRA if you earn more than $10,000.

Partial Financial Hardship

In order to qualify for IBR you need to have a partial financial hardship. Basically, this means that the amount you’d pay under IBR needs to be less than the amount you’d pay under the standard 10-year repayment plan.

From our example, you would have a partial financial hardship since your IBR payment of $268.17 (or $402.25) is less than your 10-year standard payment of $1110.21. If this were not true, your wouldn’t qualify for income based repayment.

New Borrowers

The government considers you a new borrower if you had no outstanding balance on a Direct Loan or FFEL Program loan when you received a Direct Loan on or after July 1, 2014. This basically restricts the “new IBR” to the classes of 2015 and later. Note here that the FFEL program hasn’t disbursed new loans since June 30, 2010, so only borrowers with Direct Loans can qualify as new borrowers.

Interest Capitalization

A key point you should understand about IBR (and the other income based repayment options) is what happens to the extra interest. IBR was passed in order to make debt management easier for people with lower incomes. It’s very possible that your monthly payments under IBR could be less than the interest that accrues each month.

So what happens to that extra interest? Do you still have to pay it back? This is where the difference between interest accrual and interest capitalization comes into play.

If you find yourself in a situation where your monthly payment doesn’t cover the interest on your loans, that interest accumulates over time. This is your interest accrual. If and when your adjusted gross income increases to the point where your monthly payment is greater than the interest, any payments you make in excess of the monthly interest can be applied to previously accrued interest and then toward your principal balance. To be more exact, the difference is first applied to outstanding fees, then to accrued interest, then finally to the principal on your loan.

Even though you might be accruing interest each month based on the amount of your payments, that accrued interest won’t be added to the principal balance of your loans unless it’s capitalized. This should be avoided if at all possible, since it means that the interest you’ve already accrued on the loan will start to accrue interest itself, and your debt will start to compound.

Under IBR, capitalization occurs if:

- You no longer qualify to make payments under IBR because your income is too high (you no longer have a partial financial hardship)

- You leave the plan

- You don’t recertify your income one year

Here’s an example:

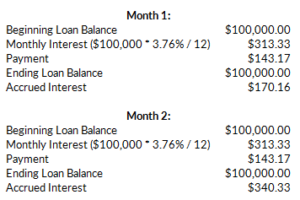

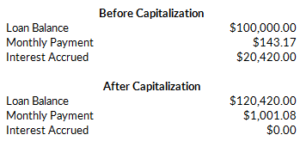

Let’s say you have $100,000 worth of federal consolidation loans and an adjusted gross income of $35,000 instead of $50,000. Let’s also assume you’re paying 3.76% annual interest. Your annual discretionary income would be $17,180, or $1431.67 per month. Your monthly payments under IBR (assuming you’re a new borrower) would be 10% of that, or $143.17. Since your payment would be less than the interest that accrues each month, the difference would be added to your total accrued interest:

Since your payment would only be $143.17, you’d accrue an extra $170.16 in interest each month. After ten years you’d still be left with the $100,000 in debt, AND have accrued $20,420 in interest. It wouldn’t be added to the principal on your loans though, unless it were capitalized.

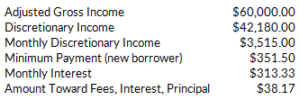

Continuing the example, if you started with a salary of $35,000 and discretionary income of $17,180, but then got a raise to $60,000, your monthly payment would be $351.50:

You’d still qualify for IBR, since $351.50 is less than you’d pay under the 10-year plan ($1,001, using 3.76% interest instead of 6%). The difference between your payments and the monthly interest is $38.17, which would first be applied to outstanding fees, then accrued interest, and finally your principal.

So how does it look if the interest is capitalized? Let’s say that you forget to recertify your income one year, which causes the interest to capitalize.

If you’d been in the system for 10 years and accrued $20,420 in interest, it would be added to your principal balance. Your monthly payment would also revert to what it would have been under the 10-year repayment plan using your original loan balance:

Of course, you could recertify immediately and go back to making IBR payments of $143.17. But at that point the damage would already have been done – you’d have just added $20,420 to your principal.

Interest Subsidy

Another helpful feature of IBR is the interest subsidy. If your monthly payments don’t quite cover the interest, the government will pay the difference on your subsidized loans in the first three years. On unsubsidized loans (and after three years of subsidized loans) the extra interest will accrue each month as described above.

Who is Eligible

As discussed above, you need to have a partial financial hardship based on your discretionary income to qualify for IBR.

In addition, only certain loans are eligible. Basically, any loan made to parents or consolidation loans that repay loans made to parents are ineligible. All other federal loans will qualify:

Loans Eligible for IBR:

- Direct subsidized & unsubsidized loans

- Direct PLUS loans made to graduate or professional students

- Direct consolidation loans that didn’t repay any PLUS loans made to parents

- Subsidized & unsubsidized Federal Stafford Loans from FFEL program

- FFEL PLUS loans made to graduate or professional students

- FFEL consolidation loans not repaying PLUS loans made to parents

- Federal Perkins loans, but only if they’re consolidated

Loans Ineligible for IBR:

- Direct PLUS loans made to parents

- Direct consolidation loans that repaid PLUS loans made to parents

- FFEL PLUS loans made to parents

- FFEL consolidation loans that repaid PLUS loans made to parents

When IBR is a Good Idea

Despite all of IBR’s benefits, the more recent pay as you earn (PAYE) and revised pay as you earn (REPAYE) options are usually more attractive to borrowers. That said, IBR is the one income based repayment option that allows FFEL loans. While you can consolidate FFEL loans in order to make them eligible for PAYE and REPAYE, consolidation isn’t always the best option. For that reason, IBR is still a worthy alternative for borrowers with existing FFEL loans who don’t want to consolidate.

Another good reason to select IBR is if you don’t qualify for PAYE. Only borrowers who didn’t have a loan balance prior to October 1, 2008 AND took out a new loan after October 1, 2011 are eligible for PAYE. This essentially limits the program to the class of 2012 and later. For borrowers who don’t want to enroll in REPAYE and don’t qualify for PAYE, IBR is a great alternative.

How You Can Sign Up

To sign up for IBR you can apply online at studentloans.gov. You’ll need to prove your income, which can be done using the IRS retrieval tool as long as you filed a tax return in the last two years. You can also fill out a paper application if you prefer. Just keep in mind that you need to recertify your income each year. Forgetting to recertify will mean that any accrued interest is capitalized and your monthly payment will jump. Student loan servicers are notorious for making clerical mistakes, so make sure to keep hard copies of everything so have a paper trail in case you need it.

Other Things to Consider

A lot of borrowers have questioned the stability of IBR, PSLF, and other aspects of the student loan repayment system. Some are concerned that the system will be changed after we get a new president.

IBR was passed by an act of Congress. Thus, we should view it as relatively stable since it would take another act of Congress to get rid of it. REPAYE, on the other hand, was passed by executive order. So if a new president wanted to get rid of REPAYE, it could also be done by executive order and completely bypass Congress.

Although none of these programs are guaranteed to last forever, we should consider IBR as more stable than REPAYE.