What is Income Contingent Student Loan Repayment?

Income contingent repayment (or ICR) is the oldest of the four income driven student loan repayment options. Originally passed by Congress in 1994, ICR was the government’s first attempt to reduce the burden of student loans by tying monthly payments to borrowers’ adjusted gross income.

While helpful when it was first introduced, ICR has been overshadowed by the other four options rolled out since then. Today, ICR is all but obsolete unless there is a Parent PLUS Loan involved.

How it Works

ICR gives borrowers another option if the monthly payments from the 10 year standard repayment plan are too costly. When borrowers enter ICR, their monthly payment is calculated based on their adjusted gross income and the amount they’d otherwise pay over a 12 year repayment plan.

More specifically, monthly payments under ICR are the lower of:

- 20% of your discretionary income, or

- the amount you’d pay under a standard 12-year repayment plan, multiplied by an income percentage factor

This income percentage factor ranges from 55% to 200% based on adjusted gross income: the lower your AGI, the lower the income factor and the lower the output. It’s updated each July 1st by the Department of Education, and can be found with a quick Google search.

An interesting point to note here is that the income percentage factor ranges all the way up to 200%. It’s possible (whether using 20% of discretionary income or the second calculation) for your monthly payment under ICR to exceed what it would be under a standard 10 year repayment plan. This differs from IBR and PAYE, where your payment is capped when this happens (at what it would have been under the standard 10-year plan).

Discretionary Income

All four income driven repayment options use discretionary income to calculate monthly payments. Income contingent repayment uses a slightly, less borrower friendly calculation.

Rather than take the difference between your adjusted gross income and 150% of the federal poverty line in your area, ICR takes the difference between your adjusted gross income and 100% of the federal poverty line in your area.

This means that your discretionary income under ICR is higher than it is under IBR, PAYE, and REPAYE. Along with the fact that ICR uses 20% of your discretionary income instead of 10% or 15%, your monthly payment under ICR could be significantly higher than under the three alternatives. You can look up the poverty line in your area through the Department of Health & Human Services.

Here’s an Example:

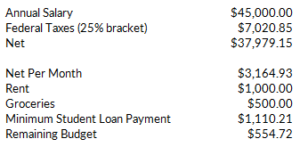

Let’s say you’re a new graduate, and your six month grace period is about to expire. You’ve accumulated $100,000 in federal student loan debt, and just got hired at a job that pays $45,000 per year. The interest on your loans is 6% per year.

If you stuck to the standard 10-year repayment plan, your monthly payment would be a hefty $1,110.21. This could be problematic, since your gross monthly pay would only be $3,750. You’d only be left with $554.72, after paying a modest rent of $1000 and grocery bills of $500:

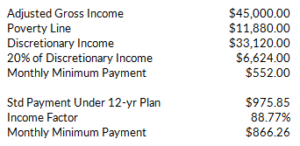

If you opted for ICR your could reduce your monthly payment by quite a bit. Your payment would be the lower of 20% of your discretionary income, or the standard 12-year payment amount multiplied by your income factor.

If the poverty line in your area is $11,880, your minimum monthly payment would be the lower of $552 and $866.26:

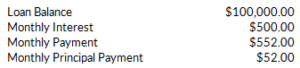

Of course, by lowering your payment you’d extend the time it’d take to repay your loans. By paying just $552 per month, it’d take you over 23 years to repay your loans as opposed to the original ten, since most of your payment would be devoted to interest alone:

Forgiveness

ICR does offer loan forgiveness after 25 years of qualifying payments, so don’t feel like you’ll be stuck with income driven payments forever. Keep in mind that any amount forgiven is counted as taxable income, if you’re not enrolled in public service loan forgiveness. This can lead to a big tax bill for lower income borrowers, so be sure to keep tax implications in mind.

Spouses

Just like IBR and PAYE, if you’re married your spouse’s income and debt will be considered if you file your taxes jointly. You can exclude your spouse’s income and debt by filing separately.

Keep in mind that filing your taxes separately generally means you’ll pay more in tax than you would filing jointly. Additionally, you can’t contribute to a Roth IRA if you file separately and make more than $10,000.

Interest Capitalization

Interest capitalization is an important topic, and another reason why ICR falls short of IBR, PAYE, and REPAYE. If your monthly payments don’t cover the interest on your loans, the difference will accrue each month. But rather than capitalizing if you forget to recertify your income or leave the plan, interest will automatically capitalize under ICR each year.

For lower income borrowers this can add up quickly. Fortunately there is a limit though, to 10% of your original loan balance at the time you entered ICR.

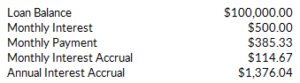

Back to our example, let’s assume your adjusted gross income is $35,000 instead of $45,000. This would make your monthly payment $385.33 instead of $552, which wouldn’t cover the monthly interest:

Each month you’d accrue $114.67 in interest, which would capitalize at the end of the year. And if your income stayed at $35,000, $1,376.04 would be added to the principal balance of your loans each year until it reached the cap of $110,000. You’d reach this point after 8 years.

Interest Subsidy

There is no interest subsidy under ICR. If your monthly payment doesn’t cover the monthly interest, that interest will always accrue. This is another shortcoming of ICR when compared to IBR, PAYE, and REPAYE, as the government will pay on some loans under all three for a limited time.

Who is Eligible

Unlike IBR and PAYE, any borrower with an eligible loan type can utilize ICR. You don’t need to have a partial financial hardship. This also means that your monthly payment could end up being more than it would otherwise be under the 10-year standard repayment plan.

Loans Eligible for ICR:

- Direct subsidized & unsubsidized loans

- Direct PLUS loans made to graduate or professional students

- Direct consolidation loans

Loans Eligible for ICR if consolidated:

- Direct PLUS loans made to parents

- Subsidized & unsubsidized Federal Stafford Loans

- FFEL PLUS Loans made to graduate or professional students

- FFEL PLUS Loans made to parents

- FFEL Consolidation loans

- Federal Perkins Loans

*Note that Direct and FFEL Consolidation Loans that repay Parent PLUS Loan are eligible for ICR. This is not true of IBR, PAYE, or REPAYE.

Loans Ineligible for ICR:

- Parent PLUS Loans (but they can become eligible by consolidating)

When ICR is a Good Idea

As mentioned above, ICR is nearly obsolete with the additions of IBR, PAYE, and REPAYE. If you’re looking to reduce your monthly payments, those three programs will almost certainly provide better terms. The one circumstance where ICR is the best option is if there are Parent PLUS Loans involved. None of the other income driven repayment options allow Parent PLUS Loans, making ICR the best option by default. If you’re not repaying Parent PLUS Loans (or consolidation loans that repaid Parent PLUS Loans), look to the other income driven options.

How You Can Sign Up

To sign up for ICR you can apply online at studentloans.gov. You’ll need to prove your income, which can be done using the IRS retrieval tool as long as you filed a tax return in the last two years. You can also fill out a paper application if you prefer, which would require you to include a paper copy of your tax return. Make sure you keep hard copies of everything you submit, since Student loan servicers are notorious for making clerical mistakes. Best to have a paper trail handy just in case you need it.

Other Things to Consider

Again, ICR is kind of an anachronistic repayment option. I wrote this post because I think it’s important everyone understands their options, but I’d never recommend ICR in this day and age unless there were a Parent PLUS Loan involved.