If you’ve ever invested in a mutual fund, you may know that they’re required to distribute at least 95% of their capital gains to investors each year. You may also know from experience that these gains are not always welcome since they come with a tax liability attached.

More often than not these capital gains are not large enough to cause investors to stir. But every year there are a few funds that pass massive unwanted gains on to investors, leaving them with a big, stinky tax bill.

This post may be slightly tardy given that some mutual fund families have already distributed their year end capital gains. Nevertheless, it’s an important topic that you should be aware of and keep an eye out for.

If your objective is to minimize your tax bill (hint: it probably should be) you’ll want to know about upcoming distributions at the end of each year, and avoid them when it makes sense. This post will cover exactly what capital gains distributions are, why mutual funds distribute them, and when and how you might want to avoid them.

Mutual Funds Capital Gains Distributions: What They Are

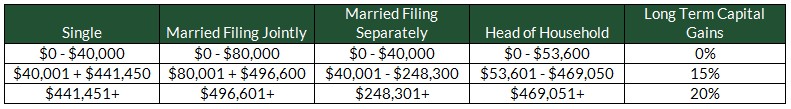

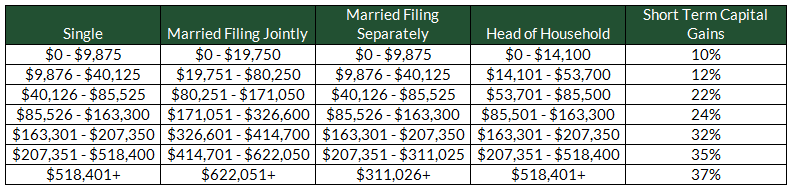

Mutual funds have capital gains just like we do as individual investors. Any time a mutual fund you own sells a security at a gain – whether it be a stock, bond, or other asset, that gain is taxable. And since mutual funds are technically pass through entities, they’re required to pass at least 95% of their net gains to investors. If these gains come from securities held for longer than a year, they’re considered long term capital gains, and taxed at favorable rates (in our current tax structure, at least):

But if the gains result from securities held for 365 days or less, short term capital gains apply at the same rate as your ordinary income:

But Aren’t Capital Gains a Good Thing?

The confusing thing here is that many of us assume that all capital gains are a good thing. We all want the mutual funds we buy to turn a profit, so it’s easy to believe that if a fund is producing capital gains it must be doing something right.

By and large that assumption holds true, gains are much better than losses. But, there is a pretty glaring caveat when we consider the taxability of those distributions and how they affect our net returns.

Remember that distributions from a mutual fund directly reduce that fund’s net asset value, regardless of their character (long term capital gains, short term capital gains, qualified dividend, return of capital, etc.). And since some capital gains distributions stem from successful investments and appreciation that occurred before you purchased the fund, you’d owe taxes on gains you didn’t even get to enjoy!

Here’s an example:

Let’s say you decide to buy a mutual fund with $10,000 of extra cash you have laying around. Let’s also say that this mutual fund made the wise decision to buy shares of JP Morgan during the depths of the financial crisis in 2009 for $28 per share. Today those shares are worth $85, implying an unrealized gain of $85 – $28 = $57.

If the fund sold the shares and realized this gain, it would be forced to pass it to its investors if there were no other offsetting losses for the year (capital gains are always netted against losses). In turn, investors in the fund would receive a long term capital gain since the investment was held for longer than a year.

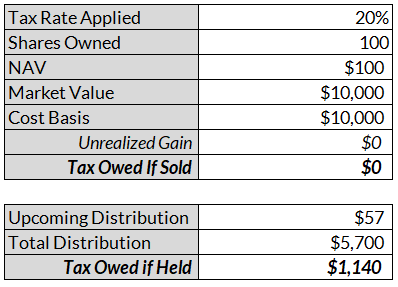

Let’s make a few more assumptions. First, let’s assume the net asset value of this fund is $100 before the distribution. If you invested $10,000 in the fund, you’d own exactly 100 shares. Let’s also assume that there are currently 1,000,000 shares of the fund in existence, and the fund owns 1,000,000 shares of JP Morgan stock. This means that each share of the fund that you own contains exactly one share of JP Morgan.

After selling the JP Morgan position, the fund would have a $57 capital gain per share to distribute to investors. After the distribution, the fund’s net asset value would fall from $100 all the way to $43.

And after investing $10,000 in the fund, you’d be left with:

- A taxable gain of $5,700

- 100 shares of a $43 fund, or a $4,300 investment

If you fell into the top tax rate of 39.6%, you’d be taxed 20% on your long term capital gains. After paying taxes on the $5,700 distribution, you’d be left with $5,700 * (1 – 20%) = $4,560. And just by virtue of receiving this taxable distribution, your $10,000 investment would now leave you with only $4,560 + $4,300 = $8,860, implying a return of -11.4%!

Automatic Reinvestment

Many investors prefer to have their distributions automatically reinvested into the same fund. Logistically this can make a lot of sense, since it saves you the trouble of reinvesting cash every time a fund pays a dividend or distributes a capital gain. That doesn’t insulate you from the tax implications though.

In our example, if you elected to have your distributions reinvested, your $5,700 distribution would be used to buy more shares of the fund at the new net asset value of $43. This would net you an extra $5,700 / $43 = 132.558 shares, meaning your total position (including your original investment) would be 232.558.

At a $43 net asset value, 232.558 shares would be worth exactly $10,000. But, you’d still be left with the big tax bill for the $5,700 distribution.

The Worst Time to Buy a Mutual Fund

If you’d purchased the fund from our example back in 2009 or earlier, you’d have enjoyed the fund’s appreciation resulting from it’s successful investment in JP Morgan. If this were the case I’m guessing you wouldn’t mind receiving the taxable distribution, since your investment in the fund would have been highly profitable on its own.

Let’s say the net asset value of the fund was $40 in 2009. If you’d owned shares since then, paying taxes on a $57 gain wouldn’t be so bad since your gain from the fund would be $100 – $40 = $60.

But if you’d just picked up shares of the fund recently, you’d have completely missed the long term appreciation. You’d be walking right into the big tax bill resulting from the fund’s success without actually enjoying any of the fund’s success!

Instead of purchasing the fund for $40 in 2009, what if you bought it for $95 just six months ago? You’d have a $5 gain per share, but owe tax on $57 of long term capital gains.

All in all, this makes it important to track the upcoming capital gains distributions from funds you own or are considering purchasing. Since capital gains are typically distributed in December (and sometimes late November), be wary of buying new funds at the end of the year.

Guidance From Mutual Fund Management

By and large, mutual fund managers are cognizant of how taxable gains affect shareholders. And since all managers want their funds to be as “marketable” as possible, nearly all make a significant effort to avoid dumping huge gains on shareholders – especially short term gains.

But sometimes they’re unavoidable. When funds experience redemption requests from investors, managers are often forced to liquidate positions they’d prefer to hold onto.

Fortunately, mutual funds are generally pretty good at estimating and communicating their capital gains distributions for the year in advance. Nearly all post the relevant information on the fund family’s website. Here’s an example from Vanguard. Many funds give investors guidance as early as September, leaving you with plenty of time to make an informed investment decision.

ETFs

Exchange traded funds (ETFs) are similar to mutual funds in many ways, but when it comes to capital gains they tend to be more tax efficient. Since exchange traded funds trade over an exchange, purchases and sales of ETFs are not executed by the sponsor of the fund – they’re traded with a market maker or another investor. This means that when investors sell shares of ETFs they’re not asking a fund company for a redemption. They’re simply selling the same security to another investor.

Without getting overly technical, ETFs are created and destroyed by authorized participants, who are all large banks & brokerage firms. To create shares, an authorized participant buys the underlying securities that comprise an ETF, places them in trust, and then is free to sell shares of the ETF on the open market. Shares of ETFs are destroyed when this process is reversed.

This means that the only actual redemption requests come from authorized participants. Not every day investors like you and me. And from a tax perspective, this redemption process (the creation and destruction of ETF shares) occurs via “like-kind transactions”. Authorized participants either deposit an ETF’s underlying securities in trust to create shares, or withdraw them to destroy shares. They’re not bought or sold like they are in a mutual fund.

And since like-kind exchanges are not taxable to investors, ETFs become a very tax efficient investment vehicle, and distribute taxable capital gains far less frequently than mutual funds do.

It’s still important to track the ETFs you own, since some of the more obscure funds (that hold illiquid securities) will be forced to distribute capital gains from time to time. But by and large, the main culprits of capital gains liabilities will be mutual funds.

How to Minimize the Tax Hit From Distributions

So you’ve got a fund that’s about to drop a big fat taxable distribution on you. What do you do?

Basically you have two options:

- Dump it before receiving the distribution

- Bite the bullet, hang onto the fund, and pay the tax

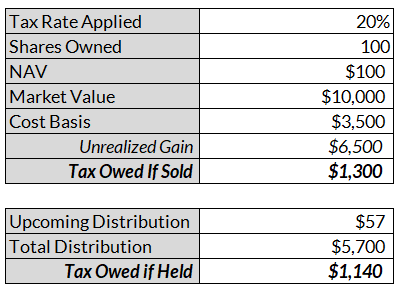

If you have a sizable unrealized gain in the fund itself you’ll owe tax on that gain if you decide to sell. So, the logical thing to do would be to compare the tax implications of selling the fund to the implications of hanging onto it.

Let’s go back to our example of the fund with a $57 distribution coming up.

Remember, you own 100 shares of a $100 fund that’s about to distribute a $57 long term capital gain. If you’d just bought the fund for $100, you’d probably want to sell it before you received the distribution, since you’d owe less in taxes:

On the other hand, if you’ve held the fund for several years you may have a large unrealized gain. If you’d picked up the shares several years ago for, say, $35 per share, your basis would be $3,500 and you’d be better off taking the distribution:

It’s also possible you have an unrealized loss that you could harvest. Remember that you can use up to $3,000 per year of realized losses to offset your income. And if you hold a mutual fund at a loss that’s about to distribute a capital gain, it could be a great opportunity to sell the fund and harvest the loss.

If you do decide to sell one or more of your funds to avoid a distribution and/or harvest a loss, make sure to heed the wash sale rule. You can always buy back the same fund in the future to maintain a consistent portfolio & asset allocation, but according to the wash sale rule you won’t be able to deduct the loss if you do so within 30 days.

Resources to Help

All in all, every investor that holds mutual funds or ETFs should keep an eye on potential distributions prior to year end. (This doesn’t apply if your funds are held in a tax advantaged retirement account like an IRA, Roth IRA, or 401(k) plan, of course. You won’t pay tax on distributions in these accounts anyway).

In my financial planning practice, I build a list of each mutual fund and ETF that my clients own and check to see whether there’s an upcoming distribution. Each fund family posts information on their funds, and there are also resources that compile all the pertinent information, like Capgainsvalet.com.

Once I compile a list of funds with upcoming distributions, the next step is to compare the cost of holding the fund and receiving the distribution to the cost of selling it. You’ll need to make an assumption about which tax bracket you’ll be in for the year, along with what any other transaction costs might be.

The list funds my clients own is pretty long, making the exercise a bit of a chore. Most individual investors don’t own more than a handful of funds though, so it shouldn’t take you too long if you’re doing it on your own.

In the end, there’s a good chance you don’t own any funds that will distribute material gains this year. Nevertheless, every year there are a handful of funds that drop large tax bombs on their investors, whether due to redemption requests or other reasons. Tax conscious investors should make sure to stay on top of their mutual fund holdings to ensure it doesn’t happen to them.

What do you think? Do you track the capital gains distributions on the funds you own? What helps you stay on top of them all?