What’s the most common piece of retirement advice you’ve ever heard? I bet it has something to do with tax advantaged retirement savings. Most people are inundated with voices telling them to start saving early and take advantage of tax deferrals. It’s solid advice. Saving tax deferred money through IRAs, 401(k) plans, and other retirement vehicles is a wonderful way to grow your wealth over time.

The downside? Those pesky withdrawal penalties. The IRS will typically ding you 10% if you withdraw from these accounts before turning 59 1/2. This can pose a problem if you’re considering an early retirement. Fortunately there are a few loopholes. eight of them, in fact:

- Roll withdrawals into another IRA or qualified account within 60 days

- Use withdrawals to pay qualified higher education expenses

- Take withdrawals due to disability

- Take withdrawals due to death

- Use withdrawals for a qualified first-time home purchase up to a lifetime max of $10,000

- Use withdrawals to pay medical expenses in excess of 7.5% of adjusted gross income

- As an unemployed person, take withdrawals for the payment of health insurance premiums

- Take substantially equal periodic payments pursuant to rule 72t

For those of you interested in an early retirement, the final loophole is likely the most interesting to you.

According to rule 72t, you may take withdrawals from your qualified retirement accounts and IRAs free of penalty, IF you take them in “substantially equal period payments”.

This post explores how.

Rule 72t

Rule 72t allows you take substantially equal periodic payments (SEPPs) from your accounts free of penalty. No disability, death, or unemployment required. All you need to do is agree to take consistent withdrawals each year for the rest of your life, based on IRS calculations.

This opens a lot of doors, since you can theoretically start distributions from your retirement accounts whenever you want. It can also be limiting. Once you begin taking SEPPs, you’re required to continue for 5 years or until you turn 59 1/2 – whichever is later.

Deviate from the prescribed withdrawals and you’ll incur the dreaded 10% penalty PLUS back interest. This applies to mistakes when calculating your withdrawals too, which is why many advisors discourage taking SEPPs altogether.

Before you pull anything from a retirement account, you’ll first need to calculate the exact amount of your SEPP. There are three methods the IRS allows you to choose:

Fixed Amortization Method

With this method, you’ll amortize your annual payments in level amounts over a specified number of years. Just like a mortgage, the idea is that you’ll work your account balance down to $0 by the end of the payment period. The time frame you’ll use is your life expectancy according to IRS tables. There are three mortality tables you can choose from:

- Single Life Expectancy

- Uniform Life Expectancy

- Joint Life and Last Survivor Expectancy

All three tables can be found on the IRS website. You’ll need to search for the most current tables, since they do change periodically.

Also like a mortgage, you’ll need to plug in an interest to calculate the payment. You have some discretion here. You can choose any rate you wish, as long as it doesn’t exceed 120% of the federal mid-term rate from either of the two months preceding the month you start distributions.

Here’s an example:

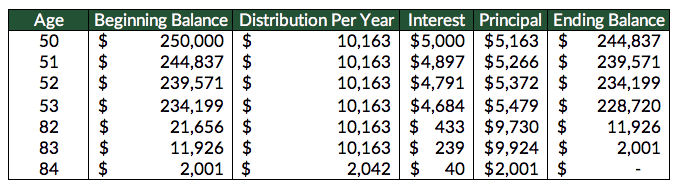

Let’s say that Mike is 50 years old and wants to retire early. His life expectancy according to the current IRS tables for a single life expectancy is 34.2 years. The current federal mid-term rate is 2% (which he uses), and Mike’s IRA account balance was $250,000 on December 31 of the previous year.

This is what his amortization table would look like over the first few years. Starting at $250,000 and earning 2% per year, $10,163 is the amount he’d need to withdraw each year to zero out the account in 34.2 years:

Annuity Table Method

Also known as the fixed annuitization method, the annuity table method calculates annual distributions using an annuity factor – similar to what an insurance company would use to determine annuity or pension payouts. This method is similar to the amortization method in that you’ll take equal annual distributions from then on. It’s also a little more complicated.

The IRS explains the annuity factor you’ll use as “the present value of an annuity of $1 per year for the life expectancy of the account holder”. Just as in the amortization method, life expectancy used is published in IRS tables, and you select an interest rate based on the federal mid-term rate.

The easiest way to calculate the annuity factor is by using Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets, or a financial calculator. Using our example above, Mike’s life expectancy is 34.2 years. So, using one of these tools, we want to ascertain the present value of an annuity of $1 per year over a life expectancy of 34.2 years.

This is the formula we’d use in Excel: =PV(Rate, Number of Periods, Payment, Future Value, Type). In Mike’s example, =PV(2%, 34.2, $1, $0, 0) gives us an annuity factor of -24.6.

Mike’s annual distribution would then be $250,000 / 24.599 = $10,162.85. He’d then continue withdrawing $10,162.85 each year.

Requirement Minimum Distribution Method

The RMD method is the easiest to calculate, but results in the lowest annual distribution. You’ll also need to recalculate your withdrawal amount each year.

Rather than use an amortization schedule or annuity factor, the RMD method simply divides your account balance every year by your life expectancy. You will need to look up your life expectancy in the IRS tables each year, but the calculation is straight forward. It’s also a great method to use if you expect your account value to fluctuate widely, since you recalculate your withdrawal annually.

In our example, Mike would take his account balance of $250,000 on December 31 of the previous year and divide by 34.2. His first distribution would be $250,000 / 34.2 = $7,309.94.

Let’s say at the end of the first year, on December 31st, his account balance has grown to $260,000 (including the distribution). His life expectancy would then be 33.2 (assuming the IRS tables haven’t changed), meaning Mike should withdraw $260,000 / 33.2 = $7,831.33.

Keep in mind here that Mike’s RMD factor is based on his age, and decreases each year. Since this is the denominator in the equation, that means that his distribution will get larger every year as long as his account continues to grow.

Comparing the Options

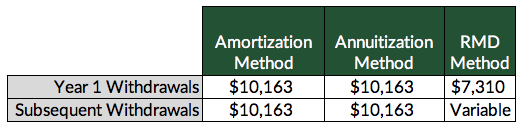

Typically the amortization method and annuity payout method will yield similar distribution amounts. They’re also both fixed year to year. The RMD method requires a recalculation each year, which can be beneficial in some circumstances.

In Mike’s situation he’d have the following options:

It’s OK if these calculations seem confusing. There are many resources out there to help you run the numbers. Bankrate.com has a solid 72t withdrawal calculator, and your tax advisor should also be ready and able to help.

Changing Options

Whereas you have some discretion over which method you choose to begin with, you have very little flexibility after you start taking payments. The amortization and annuitization methods require to calculate your payment in year 1, and then continue using that payment from then on.

The amortization and annuitization methods also allow you to change to the required minimum distribution method later on. From that point forward, you won’t be allowed to change methods again. If you select the required minimum distribution method to begin with, you’re not allowed to change calculation methods at all.

Taking Distributions

Once you calculate the amount you’re required to withdraw in year 1, the rest isn’t difficult. You’ll simply liquidate investments in your account if you need to, and request the withdrawal from your broker or custodian.

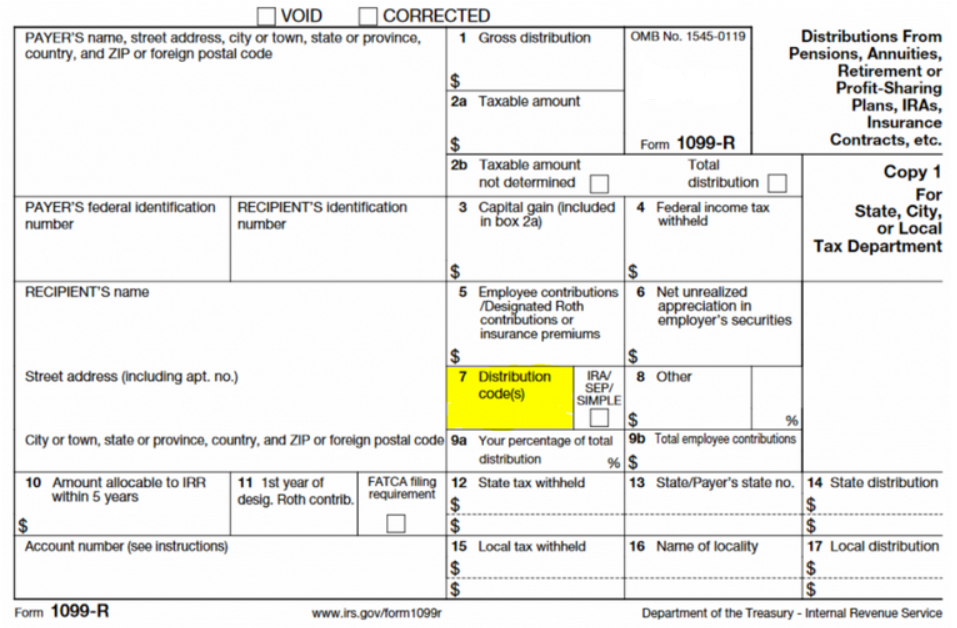

Since the transfer will be coming from a qualified account, you’ll owe tax on the distribution. As such, your custodian will be required to send you a 1099-R form at the end of the year.

1099-R forms have a section (box 7) that tells the IRS know whether your distribution qualifies for an exception to the 10% early withdrawal penalty. A code of ‘1’ means you’re taking a distribution before 59 1/2, and your custodian doesn’t know about any exceptions. This doesn’t mean that they are refuting your claim, only that they don’t know you’re taking SEPPs pursuant to 72t.

With a code of 2, your custodian tells the IRS that you’re taking an early distribution that qualifies for an exception. Again, your custodian isn’t rendering an opinion on the validity of your distribution. They’re only communicating your purpose.

If your 1099-R is marked 2, you won’t need to make additional filings. If it’s marked 1, you’ll need to file Form 5329 with the IRS. Since the IRS won’t know that your distribution qualifies as a 72t SEPP, you’ll need to tell them yourself.

When taking your withdrawals each year, it’ll help to speak with your custodian. Many firms have forms you can fill out to communicate your intent to take SEPPs. Others have staff on hand to help you make the calculations and ensure you don’t make mistakes with the withdrawal amounts. Regardless of how yours is set up, you can save yourself some time by speaking with a rep before taking any money out.

[Click here to download Above the Canopy’s Retirement Readiness Checklist]

When You Should Take 72t Distributions

Many tax and financial experts strongly discourage people from taking 72t distributions. The logic is that account balances in tax deferred vehicles should be left alone to grow. Experts think that by withdrawing funds early, you’ll increase your likelihood of running out of money in later years. Others others advise their clients to steer clear since it’s pretty easy to make a mistake that could be penalized later.

While I agree with the sentiment (generally we want to keep funds in tax advantaged accounts), early withdrawals are a necessity for many people, and part of a well structured retirement plan for others. Here are some situations where taking 72t distributions might be a good idea:

- You have a well thought out retirement plan

- You’re good at budgeting

- Your assets are spread across several different accounts & locations

- You’ve thought about a long term tax strategy

- You’re comfortable with the commitment

- You know what you’re doing

When You Shouldn’t Take 72t Distributions

Again, the decision to take a 72(t) distribution should not be taken lightly. Here are some red flags:

- You’re not totally clear what your retirement path looks like

- You have trouble staying consistent with a financial plan

- You have other funds to draw income from first

- You want to retire early but aren’t sure where your retirement income will come from

72(q) Distributions

While 72(t) applies to early withdrawals from a retirement account, 72(q) applies to early withdrawals from a non-qualified annuity.

Annuities are considered qualified when they’re held in a qualified retirement account. This might be a 401(k), IRA, 403(b), TSA, or defined benefit pension plan. Annuities held in these types of accounts are generally paid for with pre-tax dollars.

In contrast, annuities are non-qualified any time they’re not used to fund a tax advantaged retirement plan or IRA. Contributions to non-qualified annuities are paid for with after-tax dollars, and premiums are not deductible from gross income when reporting income tax.

If you hold a non-qualified annuity, you’re also subject to the 10% penalty if you take withdrawals before 59 1/2. If this is you, you can set up 72(q) distributions as opposed to 72(t) distributions. The parameters are substantially the same.

Some Suggestions When Taking 72t Distributions:

- Keep copies of the account statements you use as the basis for your calculations. You’ll want proof in order to justify your withdrawals if you’re audited by the IRS down the road. Keep everything for at least seven years, as you should for all your financial & tax documents.

- Communicate with your custodian when taking SEPPs, and ask about their process. There may be a chance to file paperwork beforehand and influence how they mark your 1099.

- Don’t round when figuring out your withdrawals. Calculate everything down the penny.

- Most people will want to consult a financial planner when considering 72(t) distributions, and a tax consultant when calculating the annual withdrawals. 72(t) distributions can be very convenient, but cost you a lot of flexibility in the long run. And given the repercussions of making a mistake, consulting a team of experts is almost certainly worthwhile.

FAQs:

What happens if I don’t take a prescribed withdrawal?

If you begin taking substantially equal periodic payments under rule 72t, you must continue to do so for at least 5 years or until you turn 59 1/2 – whichever is later. If for any reason you don’t take the prescribed withdrawal (you stop, make a mistake, etc.) there will be IRS penalties.

The internal revenue code imposes the standard 10% early withdrawal penalty plus interest, without exception. In addition, if the mistake is found in an IRS audit there could be penalties for substantial underpayment and/or filing a fraudulent return. This can tack on as much as 50% in additional penalties.

If you realize you’ve made a mistake, it’s always best to be forthcoming with the IRS. And since the repercussions can be severe, most people elect to have a tax advisor assist them when calculating annual withdrawals.

Can I change calculation methods?

After you start taking 72t distributions, you may only alter your calculation method in limited situations. If you use the annuitization of amortization methods you may change to the RMD method at a later date exactly once. At that point you must continue using the RMD method. If you start by using the RMD method, IRS rules prohibit you from changing course later.

Do I have to notify my custodian or broker that I’m taking 72t distributions?

No, but it’s a good idea to. You may be able to avoid filing additional forms with the IRS. See the next question.

Do I have to file anything with the IRS?

Possibly. Any time you take a distribution from an IRA you’ll receive a 1099-R from your trustee or custodian.

Your custodian will mark box 7 with either a ‘1’ or a ‘2’. Marking a 1 indicates that your withdraw is an “Early distribution with no known exception.” Marking a 2 indicates “Early distribution, exception applies under age 59 1/2.”

If your custodian marks a 2, you won’t need to file anything since the IRS knows you qualify for an exception to the early distribution penalty. If they mark a 1, you’ll need to file form 5329 in order to notify them.

Before taking your withdrawals, it would be wise to call your custodian and inquire about their process for taking early distributions. They might have forms or resources to make the process easier.

I have several accounts, how does that work?

You don’t have to apply the rule to all your accounts – just the one you’re taking distributions from. If you have several IRA and/or 401k accounts, you can take 72t distributions from one account without touching the others.

This can be extremely convenient. You could theoretically split an existing account deliberately by rolling funds into a new IRA, and back in to the exact annual withdrawal you’re seeking. Just remember that once you begin SEPP’s you may not contribute or withdraw funds from the account (other than taking the annual withdrawals, of course).

Can a portion of my IRA assets be excluded?

No. You must incorporate the entire balance in each of the accounts you take distributions from. Segregation of assets within one account is not allowed. See the previous question for a workaround.

What if my account balance falls to $0?

If your account is completely depleted, you can discontinue withdrawals without incurring the 10% penalty.