With tax season now in the rear view mirror, many of us are licking our wounds after a shellacking from Uncle Sam. I heard from a lot of people this year that they owed far more to the IRS than they expected to. Come to find out, the IRS changed the withholding tables with the new tax bill. Rather than overwithholding throughout the year and getting a refund in April, thousands across the country underwitheld & had to pay out of pocket.

Another item factoring into last year’s fat tax bills was capital gains. Mutual funds and ETFs distribute capital gains back to shareholders, which are taxable based on the amount of time the fund owned the holding. As an investor, receiving an unwanted taxable distribution can be inconvenient.

As a reader recently put it: “For the second year in a row I’ve gotten killed with large capital gains from my mutual funds, resulting in a large tax bill. Aside from owning stocks on my own, how can I eliminate or minimize these capital gains?”

Today’s post will answer this exact question. For those of you who’ve seen the adverse tax consequences of capital gains distributions, read on to learn a few strategies you could use to minimize the bite.

Pair Up Gains With Losses

The first strategy to consider is to match up capital gains with losses in other positions, since you’re only taxed on your net capital gains. For example, if you own a mutual fund that sends you a $10,000 Christmas present at the end of the year, you could sell another position at a loss to bring down the net amount – potentially to $0 if you found $10,000 worth of losses to offset the distribution entirely.

Capital gains and losses are recorded in the calendar year, meaning you’d need your sales to occur prior to December 31st. Since capital gains distributions from mutual funds and ETFs generally occur toward the end of the year, this gives you a rather tight window to work with.

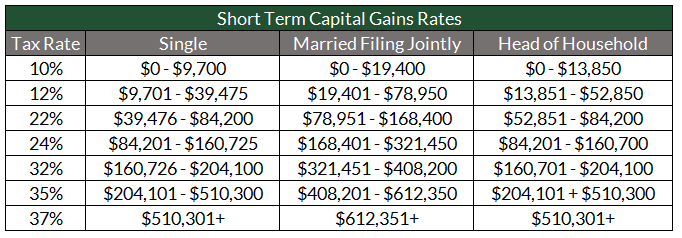

Also recall that long term capital gains are taxed at lower rates than short term capital gains. Capital gains are considered short-term if you’ve held the investment for less than one year, and are taxed at your ordinary income rates:

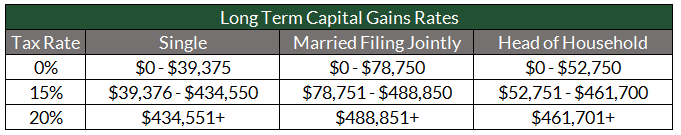

As soon as you’ve held an investment for a year or longer, they turn into long-term capital gains, taxed at the following rates:

The difference here is important to keep in mind because short term and long term gains & losses are netted against each other on your returns. Here’s how it works:

- Subtract your short term losses from your short term gains (including carry-forwards from previous years).

- Subtract your long term losses from your long term gains (including carry-forwards from previous years).

- Net your short and long term gains and losses. The result is what shows up on your return for the year. (Here’s a more thorough description of the process).

Use Tax Efficient Funds

Mutual funds have investment policies and objectives that are clearly stated in the prospectus. This is a legal requirement that mutual funds must abide by. Managers of mutual funds abide by these objectives (they’re supposed to, at least) when buying & selling securities in the fund.

Most mutual fund objectives read something like this:

“The investment objective for this fund is to achieve long term capital appreciation”; or

“The investment objective for this fund is to maximize total returns within the universe of securities that the portfolio invests”.

See anything about taxes? Me neither. Most mutual funds are concerned with maximizing return without regard for tax impact. Simply put, fund managers are rated & paid on pre-tax performance.

Unless their fund’s objective states otherwise. There is a growing set of fund families that offer tax-managed funds with strategies similar to their core fund offerings. The fund is nearly identical, but the holdings are managed in a more tax conscious manner.

Dimensional Fund Advisors offers a solid suite of tax-conscious funds that complement their core offerings. Vanguard has the same. Don’t jump into these blindly though. While tax managed funds may be helpful in reducing current tax liabilities, they may only be deferring them for a larger hit later on.

Click Here to Download the 5 Step Retirement Income Plan

Use ETFs Instead

The ETF market has exploded in recent years, and now a large portion of investment strategies offered through mutual funds are also available in an ETF. Due to a couple structural differences, ETFs tend to be far more tax efficient to investors.

In short, ETFs have far fewer taxable events. For example, a basic S&P 500 index fund will only need to buy and sell shares when the constituents of the index change. This happens quarterly as companies falling out of the S&P 500 are sold and companies entering are bought. If outgoing shares are sold at a gain, that gain must be distributed to shareholders.

When investors buy and sell shares of an ETF, they transact with other investors over an exchange – not with the mutual fund company. Hence the term “exchange traded funds”. A mutual fund is quite different. Investors in mutual funds buy and redeem shares directly with the fund manager. That means when investors decide to buy more shares of the fund, the manager has an influx of cash which it uses to buy more stock for the portfolio. But when investors sell shares, the manager may be forced to sell shares in the fund’s portfolio to meet the cash needs. Selling shares at a gain produces a taxable event, which is distributed back to shareholders pro-rata.

So to compare, capital gains in ETFs are typically only triggered when the fund’s constituents change. For mutual funds, capital gains could also be triggered by the actions of your fellow shareholders. And since fund managers are seeing huge outflows toward index funds & ETFs, it’s not surprising to see the recent capital gains distributions. According to State Street, 6.2% of all US listed ETFs distributed capital gains to shareholders, compared to more than 60% of mutual funds.

Stay on Top of Upcoming Distributions

Another alternative to avoid annual distributions is simply to sell your mutual funds before a capital gain is actually distributed. Fund companies announce upcoming distributions at least a couple weeks in advance of the record date, giving you a window to sell if you’re so inclined. The “record date” is the date the fund company uses to determine which investors will receive the distribution (dividends, capital gains, or otherwise). If you hold shares on the record date, you’ll be getting the distribution whether you like it or not.

Also be aware of the “ex-dividend” date, which is the first day that a security trades without the upcoming distribution attached to it. The ex-dividend date is typically one day before the record date for mutual funds. For our purposes, just remember that if you want to sell a mutual fund in order to avoid an upcoming capital gains distribution, you’ll need to have your order in at least two days before record date.

The downside of this strategy is that selling mutual fund holdings will trigger a taxable event of its own if you’re selling the shares at a gain. And if a fund you hold is distributing a gain you’re trying to avoid, there’s a good chance it’s in an up year when you have a gain in the holding itself.

Nevertheless, this is a strategy to keep in your back pocket. The way I typically do this with my clients is to review the upcoming distributions for all their holdings at the end of Q3 each year. You can look up announced distributions on each fund company’s site through a quick google search. There are also resources out there dedicated to tracking distributions. My friend Mark Wilson manages the site capgainsvalet.com, which tracks fund distributions and estimates upcoming announcements. They also keep a great list of consistent capital gains “offenders” that’s worth a look.

So there you have it. Four strategies to consider to reduce the impact of capital gains distributions. I’d always rather make a buck and pay taxes on it than not make a buck at all, but there’s no reason to pay any more in tax than you need to.

What do you think?

Are there other strategies you’ve used to avoid taxes on capital gains distributions?